|

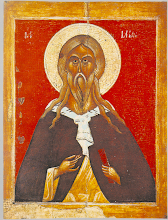

Aleksandr Sytov, Apostle St Mark, 1995 |

Saint Mark is, of course, best known as the author of a Gospel. Like Saint Luke and Saint Paul, he was not one of the Twelve Apostles and so likely never met Jesus Christ in person. Scholars believe that the Gospel of Saint Mark relates the experiences of Saint Peter, Mark’s mentor. Each Gospel has its own unique sources, emphases, and audiences. Mark writes for non-Jews who would be impressed by Christ’s miracles more than His fulfillment of Old Testament prophecies. So in Mark’s Gospel are found certain colorful details that suggest the writer was relating the words of an eye-witness. For example, in Mark 5:41 Jesus enters the home of Jairus, a synagogue leader whose daughter lay dead. Christ says to her, “Talitha koum.” Mark then tells the reader what “Talitha koum” means, presumably because his readers did not speak Aramaic. No other Gospel includes this touching detail of the untranslated words coming from the mouth of Christ that day. Mark also places other Aramaic words on Christ’s lips: “Ephphatha,” “Abba,” and “Hosanna.” (Read more.)

From Catholic Online:

Another tradition by Eusebius, accords Mark the first bishop of Alexandria. As he entered the city gates, a sandal strap broke. A shoemaker was chosen to fix the leather--Anianus. He became Mark's first disciple and convert to Yeshua, Jesus. in Alexandria. Enemies, however, sought out Mark. The writer of the Gospel of Mark after sufficient teaching, appointed Anianus bishop, and ordained three priests and seven deacons. Leaving the city, he told them to "serve and comfort the faithful brethren."

After some years, Mark returned. The Christian community had grown considerably. But his enemies had not forgotten him. They jailed him. On the following morning, Mark's neck was tied with a rope. The malefactors dragged him by the neck from Alexandria up to the little port of Bucoles until he died. They attempted to burn the body. Flames would not touch it. Christians in the community claimed the remains, burying it in a Church Mark had founded. It is said he is the first Christian martyr of the Church in Kemet. (Read more.)

|

| St. Mark the Evangelist by Il Pordenone |

The Greater Litanies traditionally begin today. From A Catholic Life:

Today is April 25, the Feast of St. Mark, and the Major Rogation. While no longer required after Vatican II, Rogation Days can still (and should) be observed by the faithful. I encourage my readers to observe these days. Fasting and penance were required, and the faithful would especially pray Litanies on this day.

Not until relatively recently, it was a requirement that this day was kept with two conventual Masses where choral obligation existed. The first, post tertiam, was the festive Mass of St. Mark the Evangelist. The second post nonam was the more penitential Mass formula of Rogation tide. For those bound to the Divine Office, the Litany was mandatory today.

What are Rogation Days?

"Rogation Days are the four days set apart to bless the fields, and invoke God's mercy on all of creation. The 4 days are April 25, which is called the Major Rogation (and is only coincidentally the same day as the Feast of St. Mark); and the three days preceding Ascension Thursday, which are called the Minor Rogations. Traditionally, on these days, the congregation marches the boundaries of the parish, blessing every tree and stone, while chanting or reciting a Litany of Mercy, usually a Litany of the Saints" (1)(Read more.)

From Catholic Saints Info:

The Jews in the Old Testament had a form of public prayer in which one or more persons would pronounce invocations of God which all those present answered by repeating (after every invocation) a certain prayer call, like “His mercy endures forever” (Psalm 135) or “Praise and exalt Him above all forever” (Daniel 3:57-87).

In the New Testament the Church retained this practice. The early Christians called such common, public, and alternating prayers “litany,” from the Greek litaneia (lite), meaning “a humble and fervent appeal.” What they prayed for is indicated in a short summary by Saint Paul in his first letter to Timothy (2:1-2). The common and typical structure of the litany in the Latin Church developed gradually, from the third century on, from short invocations as they were used in early Church services. It consisted of four main types, which were recited either separately or joined together. First, invocations of the Divine Persons and of Christ, with the response Miserere nobis (Have mercy on us). Second, invocations of Mary, the Apostles, and groups of saints, response: Ora pro nobis (Pray for us). Third, prayers to God for protection from evils of body and soul, response: Libera nos, Domine (Deliver us, O Lord). Finally, prayers for needed favors, response: Te rogamus, audi nos (We beseech Thee, hear us).

Many invocations of individual saints and special petitions were added everywhere in later centuries, and popular devotion increased their numbers to such an extent that Pope Clement VIII, in 1601, determined the official text of the litany (called “Litany of All Saints”) and prohibited the public use of any other litanies unless expressly approved by Rome.

The invocation Kyrie eleison came from the Orient to Rome in the fifth century. It soon acquired such popularity that it joined (and even supplanted) the older form of litany in the Mass of the Catechumens. Up to this day the Kyrie eleison and Christe eleison in the Mass remain as relics of the responses that the people gave to petitions recited by the deacon (before the readings) and by the celebrant (after the Gospel). Outside of the Holy Sacrifice, the Kyrie eleison was also added to the other types of litany prayers; it may still be found at the beginning and end of every litany. The Greek Rite still uses a number of actual litanies (Ektenai) in its liturgy (the Holy Sacrifice).

Many and varied are the occasions on which litanies were in use among early Christians. Besides being a part of the Mass liturgy, a litany was recited before solemn baptism (as it is today in the liturgy of the Easter vigil) and in the prayers for the dying (where it is also still prescribed). Even more frequent, however, was the use of litanies during processions, because the short invocations and exclamatory answers provided a convenient form of common prayer for a multitude in motion. This connection between litany and procession soon brought about the custom of calling both by the same term. From the sixth century on, litania was used with the meaning of “procession.” The first Council of Orleans (511) incorporated this usage into the official terminology of the Church.

Since the ancient Roman Church had many and divers kinds of processions, the litanies must have been a most familiar feature of ecclesiastical life. Litanies (processions) were held on Station days, every day in Lent, on many feasts, on Ember Days and vigils, and on special occasions (calamities and dangers of a usual or unusual kind) when God’s mercy and protection was implored with particular fervor. These latter occasions had already been observed in pagan Rome with processions to the shrines of gods at certain times of the year. Their natural features (dates, routes, motives) were part of the traditional community life. These features the Church retained in certain cases, filling them with the significance and spiritual power of Christian worship. (Read more.)

.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment