Our Lord’s descent into hell is well

attested to by divine revelation. For example, Christ says, “as Jonah

was three days and three nights in the belly of a whale, so will the Son

of man be three days and three nights in the belly of the earth” (Mt. 12:40). Further, in Acts of the Apostles,

St. Peter says, “[David] foresaw and spoke of the resurrection of the

Christ, that he was not abandoned to Hades, nor did his flesh see

corruption” (2:31). Likewise in the Apostles’ Creed we profess, “He descended into hell.”

Besides making clear that the soul of

Christ descended into hell, these texts clearly refer the descent into

hell to the Person of Christ. And this is supremely fitting. For, since

the personal union of the Word of God with both His body and soul

remained even after death, whatever could be attributed to either of

these principles of His human nature, while they were separated, was

also attributable to God the Son. Thus, in the Apostles’ Creed we

profess that He (i.e., God the Son) was buried insofar as His body was

placed in the tomb. In like manner, we profess that God the Son

descended into hell on account of His soul going to the underworld.

Connected with this, St. Thomas Aquinas

points out that it is even true to say that “during the three days of

His death, the whole Christ was in the tomb, in hell, and in heaven, on

account of His Person, which was united to His body lying in the tomb,

and to His soul-harrowing hell, and which was subsisting in His divine

nature reigning in heaven” (Compendium Theologiae,

ch. 229). Indeed, insofar as by His divine immensity the Son of God

comprehends or contains all things, we must affirm that the whole Person

of Christ is both in every place and in all places put together, yet He

is not wholly contained by any one place nor by all places put together

(Summa Theologiae, III, q 52, a. 3, ad 3um).

When reflecting on our Lord’s harrowing

of hell, it is, of course, necessary to distinguish different meanings

of the name “hell.” In its most general meaning, “hell” signifies “the

underworld,” which the Hebrews refer to as, Sheol, and the Greeks call by the name, Hades (Catechism of the Catholic Church, #633). Further, as the Roman Catechism teaches, there are three main parts to the underworld. There is gehenna,

or hell in the strict sense, which is the abode of the damned. There is

also purgatory wherein the punishments, unlike those of gehenna, are cleansing and only temporary in character. Lastly, there is that part of the underworld known as “Abraham’s bosom” (see, Luke 16:22-26).

It was in here that “the souls of the just prior to the coming of

Christ the Lord were received, and where, without experiencing any sort

of pain, but supported by the blessed hope of redemption, they enjoyed

peaceful repose” (Roman Catechism, pt. 1, art. 5).

So, into which part or parts of hell did

Christ descend and why? Taking St. Thomas Aquinas as our guide, we can

affirm both that our Lord descended into all three parts of hell and

that He descended into only one part of hell (i.e., into Abraham’s

bosom). But to see how both of these statements are true without

contradiction, we must distinguish two ways in which something can be

somewhere.

Thinking of everyday examples first, it

is true that one and the same fire is simultaneously both in the

fireplace and in every part of the room which it heats. The fire is in

the fireplace as in a proper place, while it is in every part of the

room through its effect, that is, through the heat which it produces.

Likewise, it is true that one and the same musician is simultaneously

both on the stage and in every part of the concert hall. For the

musician is on the stage insofar as that is his proper place, yet he is

also present in every part of the concert hall through his effect, that

is, through the music that he produces.

Applying this distinction to our Lord’s

descent into hell, it is true to say that Christ’s soul, through its

essence, only entered Abraham’s bosom. Nonetheless, through its effect,

Christ’s soul was in some way present in every part of hell. As St.

Thomas puts it, “being in one part of hell, his effect in some way

spread to every part of hell, just as by suffering in one place on

earth, he liberated the whole world by His passion” (Summa Theologiae,

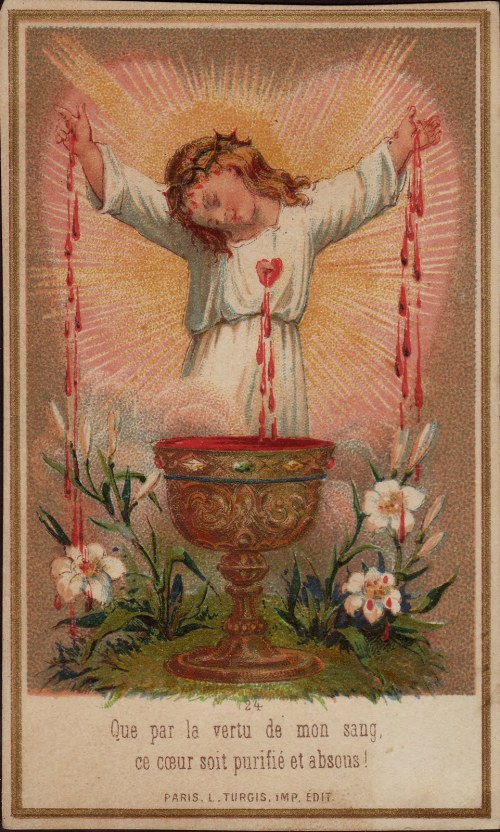

III, q. 52, a. 2). More specifically, St. Thomas teaches that the

proper effect of Christ in the underworld was the bestowal of the

beatific vision on the souls of the just waiting for Him in Abaham’s

bosom. This, properly speaking, constitutes the harrowing or despoiling

of hell. For, through granting the souls of the just the vision which

beatifies, the King of all things “robbed” hell of its most prized

possessions. But Christ’s presence in hell also had the effects of

giving hope of attaining eternal glory to the souls in purgatory and of

confounding and bewildering those in gehenna (Summa Theologiae, III, q. 52, a. 2).

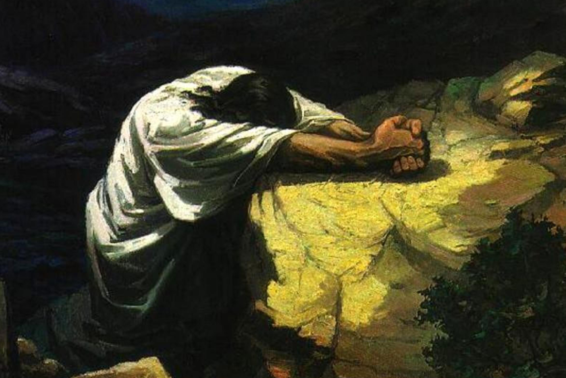

These considerations, in turn, cast some

light on the reasons for God the Son’s descent into hell. For one

thing, He went there to manifest His power and authority to the

underworld. As St. Paul writes, “at Jesus’ name every knee must bend in

the heavens, on the earth, and under the earth, and every tongue

proclaim to the glory of God the Father: Jesus Christ in Lord!” (Phil.

2:10-11). But secondly, and more importantly, our Lord came to deliver

His loved ones from their exile. He came to reward those who, from our

first father, Adam, to His own foster-father, St. Joseph, had fought the

good fight and had finished the race. The King descended into Hell in

order to bring nothing less than His own beatific vision, the very

paradise which He promised to Dismas just a few hours before (Lk. 23:43), to these just and holy souls. (Read more.)

/jesus-in-garden-of-gethsemane--mosaic--detail--glorious-mysteries-chapel--upper-basilica-of-our-lady-of-rosary--lourdes--languedoc-roussillon-midi-pyrenees--france--19th-century-677110309-5a839ae9642dca003762cc49.jpg)

.jpg/784px-The_Crowning_with_Thorns-Caravaggio_(1602).jpg)